The Adventure of the Imaginary Detective

Sherlock Holmes: The man who never lived and will never die. The poster boy of Victorian fiction, doyen of the great detectives. But who was he? Who is he, besides a Hollywood star and fixture of Christmas Day TV schedules? Why does he command such a loyal following even now, a hundred and thirty years on since he first appeared in A Study in Scarlett?

I present here, a fresh new case: The Adventure of the Imaginary Detective. Together, will be looking for clues and carefully sifting through the facts. By the end I hope we will have reached a satisfactory conclusion. But for now, I would ask that you all remain within this room until the case is resolved.

Now it is impossible to imagine the outcry that followed the death of Sherlock Holmes in The Final Problem. The Victorians wore black arm bands in the street. The national newspapers ran obituaries. 20,000 people cancelled their subscription to the Strand magazine. Except perhaps for the break up of The Beatles, there is no modern equivalent. To his fans, he was fully alive, leaping off the page, and glowing as brightly as the tobacco in his famous pipe bowl. This insatiable public appetite for Holmes perhaps was ultimately the reason why he eventually returned, never to leave us again.

But there is so much more to Holmes that the two-dimensional sleuth of popular culture. The Holmes of the original canon, the fifty six stories and four novellas, which we will confine ourselves to here, is a surprising, complicated and flawed character, foibles that only serve to make him more attractive.

‘I’ve found it. I’ve found it!’ These were the first words we hear Holmes utter in that memorable first adventure from 1887, and they echo down the years. They also serve as a manifesto. Holmes finds the solution time and again.

I stumbled into writing Sherlock Holmes fiction almost entirely by accident. My brother rang me up one day asking for a suggestion or a name for his online jewellery shop. I asked him what sort of pieces he had and he told me a about a strange ruby elephant he had acquired from an American collector. I thought for a moment and suggested the name ‘The House of the Ruby Elephant.’ Immediately this sounded to me like the name of Holmes adventure.

A quick internet search however, revealed that Anthony Horowitz had just published his Sherlock Holmes adventure: The House of Silk. I changed mine to The Adventure of the Ruby Elephants, and without so much as a plot, I began my first novel in earnest.

It begins with the escape of an elephant from London Zoo and leads Watson and Holmes on an unlikely search for lost Indian diamonds that leads them to Queen Victoria and the last Maharaja of India via rural Suffolk and Lord’s Cricket Ground.

Along the way, they encounter four sinister characters called the archangels – assassins in top hats and sharpened canes hell-bent on the destruction of Holmes and the acquisition of the diamonds. I’ve since written two more: The Jeweller of Florence, and published just last month The Adventure of the Beer Barons.

In this blog, we will learn only about the man. We will find out where he came from. We will meet his friends and his enemies. We will study his methods and try and think like him. But before we begin our investigations, a word of warning, from Holmes himself:

“It is a capital mistake to theorize in advance of the facts. Insensibly one begins to twist facts to suit theories, instead of theories to suit facts.“

So let us not speculate, but acquire our data first, and by the only means Holmes would approve: by scrupulous observation.

The precursor to Holmes

Let us first consider his origins. Sherlock Holmes did not of course simply pop out of thin air, fully formed.

Now there are many who believe, or choose to believe, that Holmes was in fact quite real. And who am I to say they’re wrong? Was he just a figment of Dr Watson’s imagination? However most agree that Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle was his creator.

Born in 1859, Conan Doyle (No hyphen) was 38 when the first Holmes story was published in Beeton’s Christmas Annual. As well as a writer of prose fiction, he was a poet, a playwright, a spiritualist and trained doctor, suggestive of course, of Dr Watson’s occupation. He was well travelled having been ship’s doctor on a whaling ship, but in the early 1880s settled down, like Watson to start a general medical practice, first with his friend, and later on his own.

However, and fortunately for us, Conan Doyle’s practice was not a success. With few patients, he filled in time by writing his stories. It is tempting to think that many of the characters that populate the adventures drew their inspiration from his list of patients. We also know he had a rival working around the corner called Dr James Watson.

Now while Conan Doyle proved a writer of great invention, and perhaps genius, he cannot however take credit for inventing the detective fiction genre.

Holmes may be the best remembered, but there were several who came before him and who are now considered the precursors to Sherlock Holmes. There was Inspector Bucket from Dicken’ Bleak House, but the most relevant to our enquiries perhaps was a character called Auguste Dupin, conceived by that master of the gothic, Edgar Allen Poe.

Dupin is now almost completely forgotten, eclipsed by the blinding light of Sherlock Holmes’ fame. Yet he reflects many of the qualities we later come to associate with Holmes. He is reclusive, eccentric and follows a rigorously scientific method. He has a superior manner, divorces himself from his emotions and regularly reveals the incompetence of the police. Does that sound familiar yet? If that’s not all, he also has a side kick who becomes the narrator of his stories.

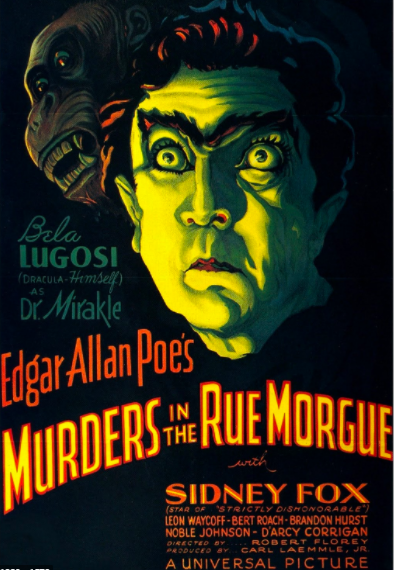

Dupin’s first appearance came in 1841 in the Murders in La Rue Morgue, a full 46 years before A Study in Scarlett in 1887. I’d like to read you a little bit to give you a taste of Dupin and his methods:

Residing in Paris during the spring and part of the summer of 1840, I there became acquainted with a Monsieur C. Auguste Dupin. This young gentleman was of an excellent—indeed of an illustrious family, but, by a variety of untoward events, had been reduced to such poverty that the energy of his character succumbed beneath it.

Our first meeting was at an obscure library in La Rue Montmartre, where the accident of our both being in search of the same very rare and very remarkable volume, brought us into closer communion. We saw each other again and again. I was deeply interested in the little family history which he detailed to me with all that candor which a Frenchman indulges whenever mere self is his theme. I was astonished, too, at the vast extent of his reading; and, above all, I felt my soul enkindled within me by the wild fervor, and the vivid freshness of his imagination.

Seeking in Paris the objects I then sought, I felt that the society of such a man would be to me a treasure beyond price; and this feeling I frankly confided to him. It was at length arranged that we should live together during my stay in the city; and as my worldly circumstances were somewhat less embarrassed than his own, I was permitted to be at the expense of renting, and furnishing in a style which suited the rather fantastic gloom of our common temper, a time-eaten and grotesque mansion, long deserted through superstitions into which we did not inquire, and tottering to its fall in a retired and desolate portion of the Faubourg St. Germain.

Had the routine of our life at this place been known to the world, we should have been regarded as madmen—although, perhaps, as madmen of a harmless nature. Our seclusion was perfect. We admitted no visitors. Indeed the locality of our retirement had been carefully kept a secret from my own former associates; and it had been many years since Dupin had ceased to know or be known in Paris. We existed within ourselves alone.

We were strolling one night down a long dirty street in the vicinity of the Palais Royal. Being both, apparently, occupied with thought, neither of us had spoken a syllable for fifteen minutes at least. All at once Dupin broke forth with these words:

“He is a very little fellow, that’s true, and would do better for the Théâtre des Variétés.”

“There can be no doubt of that,” I replied unwittingly, and not at first observing the extraordinary manner in which the speaker had chimed in with my meditations. In an instant afterward I recollected myself, and my astonishment was profound.

“Dupin,” said I, gravely, “this is beyond my comprehension. I do not hesitate to say that I am amazed, and can scarcely credit my senses. How was it possible you should know what I was thinking of?’

“Tell me, for Heaven’s sake,” I exclaimed, “the method—if method there is—by which you have been enabled to fathom my soul in this matter.’

“I will explain,” he said, “and that you may comprehend all clearly, we will first retrace the course of your meditations, from the moment in which I spoke to you until that of the rencontre with the fruiterer in question. The larger links of the chain run thus—Chantilly, Orion, Dr. Nichols, Epicurus, Stereotomy, the street stones, the fruiterer.”

You will note that Dupin has a very similar manner to Holmes, the same apparent gift for reading minds and divining the seemingly impossible. He has the same supercilious way in which he explains his method, based on the twin sciences of observation and deduction.

There is the also same dynamic between the two men as Watson and Holmes; the same balance of power – Dupin superior in intellect, the other dumbfounded by his conclusions.

The story also has a Holmesian ring of strangeness to it. The bodies of two woman are found in a locked upper room – a mother and daughter, one of whom is found in the chimney. There are deep scratches and bruises on their bodies. Shall I tell you how it ends? If not, please skip on. An orang otang belonging to a sailor living close by escapes, climbs up the lightening rod, enters the women’s room and commits the murders.

The story was later made into a film starring Bela Legosi – although as you can see from the poster, they clearly didn’t mind giving the ending away.

The key difference of course between Holmes and Dupin, is that he is a Frenchman and his stomping ground is Paris rather than Baker Street. Transplanting this character to London was a canny move on Conan Doyle’s part, but I think you will agree that he owes something of a debt of gratitude to Edgar Allen Poe.

Joseph Bell

There was a real-life inspiration too. Joseph Bell was a Scottish surgeon whom Conan Doyle worked for while at Edinburgh Royal Infirmary.

He was a pioneer in several ways, both in his habits and interests. He was one of the first experts in forensic medicine, helping the police in a number of matters including the notorious Ripper murders. But it was the fact that he based his medical work on close observation, often diagnosing patients based on tiny, almost invisible symptoms that suggests he was a model for Holmes. He would also use his powers of observation and deduction to play games where he would deduce a man’s occupation and character merely by his appearance. You can well imagine Conan Doyle as an impressionable young clerk in thrall to Bell, totally impressed and mystified by the older man’s exceptional skills and masterful manner.

Robert Louis Stevenson, who also worked for Bell wrote to Conan Doyle write to the authors after reading the first Holmes adventure. ‘Why,’ he said, ‘Holmes is based on old Joe Bell!’

So let’s get to know Holmes a little better. I have spent the last five years in the company of Sherlock Holmes. Not in the form of a box-set or with the benefit of the iPlayer but sitting inside 221b Baker Street in my guise of Dr Watson. I have had the opportunity to observe him a close-quarters in his lesser known stories: The Adventure of the Ruby Elephants, The Jeweller of Florence and the Adventure of the Beer Barons. He is infuriating, unpredictable and ferociously intelligent. Indeed the biggest problem writing a Sherlock Holmes adventure is writing about a character who is more intelligent than you are. There have been many instances where I have ceased typing and stopped in astonishment at some utterance or revelation. It is as if I am discovering the solution at the same time as my fictional alter ego.

There are a few unspoken rules when writing Sherlock Holmes’ fiction. First and foremost, you must never kill off Watson, and certainly not Holmes, for the simple reason that it would spoil the fun for everyone else. It’s worth noting that this is not a rule Conan Doyle chose to follow himself.

There are other rules too. You mustn’t tinker with the chronology. You can’t send him off to India in 1890 when we know he was in Devon. If you do set a novel further afield, you need to set it during the great Hiatus, between his supposed death and his return in the adventure of the empty house.

There’s another important rule. In the novels, he is never Sherlock. Always Holmes, except in the company of his brother, where only Mycroft is permitted to address him by his first name. This presents problems for writers who must keep finding new ways to refer to him, without writing the word Holmes on every line. You end up writing many lines such as these: ‘I regarded my friend with a weary affection.’

Now let’s us consider the man and his habits

Holmes the hedonist

Holmes was inordinately fond of his pleasures. For a man famous for his brain work, by the same measure, he did not deny himself the pleasures of the flesh. Let’s look the beginning of The Adventure of the Illustrious Client:

Both Holmes and I had a weakness for the Turkish bath. It was over a smoke in the pleasant lassitude of the drying-room that I have found him less reticent and more human than anywhere else.

This is quite typical of Holmes’ self-indulgence, and there is something of the decadent nineties that pervades all the stories. After all, this is the decade bestrode by Oscar Wilde, who memorably declared: ‘Pleasure is the only thing one should live for. Nothing ages like happiness.’

In the Adventure of the Twisted Lip, Watson finds Holmes in an opium den:

‘I suppose Watson,’ said he, ‘that you imagine I have added opium smoking to cocaine injections and all the other little weaknesses on which you have favoured me with your medical views’ On this occasion, he was in fact on business rather than pleasure.

Then there is Holmes the smoker. Pipes, cigars, cigarettes, loose tobacco. You name it, Holmes smokes it. In fact without the references to smoking, the 670,000 Conan Doyle wrote across the adventures of Sherlock Holmes would be probably be halved. Never was there a worse case of passive smoking than the one suffered by poor Dr Watson. But you see smoking is considered essential to Holmes’ brain work.

“It is quite a three pipe problem,’ he tells Watson. ‘and I beg that you won’t speak to me for fifty minutes.”

Don’t you love the precision of that? He doesn’t know the solution to the problem yet, but he knows exactly how long it will take him to get there.

This is one of my favourite descriptions of Holmes’ habits and its inextricable link with his thought processes:

A large and comfortable double-bedded room had been placed at our disposal, and I was quickly between the sheets, for I was weary after my night of adventure. Sherlock Holmes was a man, however, who when he had an unsolved problem upon his mind would go for days, and even for a week, without rest, turning it over.

He put on a large, blue dressing gown and then wandered around the room collecting pillows from the bed and cushions from the sofa and armchairs. With these he constructed a sort of Easter divan, upon which he perched himself crosses legged with an ounce of shag tobacco and a box of matches laid out in front of him. In the dim light of the lamp, I saw him sitting there, an old brier pipe between his lips, his eyes fixed vacantly upon the corner of the ceiling, the blue smoke curling up from him.

The references are exhaustive, the most famous perhaps being the fact that he kept his tobacco in his Persian slipper and his cigars in the coal scuttle. These are two of the key references for any aspiring writer of Holmes fiction. Leave them out and you will leave the fans disappointed.

Smoking is not confined to quiet moments at Baker Street. Cigar and cigarette ash are often the key to solving cases too and we learn Holmes has written monograms about identifying different types of ash.

Now of course Sherlock Holmes is all about finding solutions. But when there is no case to absorb him, he turns to a solution of quite a different kind. I’m referring of course, to Holmes’ most notorious transgression: the 7 percent solution. Conan Doyle makes no attempt to conceal Holmes’ cocaine use, appearing as it does in in the very first line of The Sign of Four.

Sherlock Holmes took his bottle from the corner of the mantel-piece and his hypodermic syringe from its neat Moroccon case. With his long, white, nervous fingers he adjusted the delicate needle, and rolled back his left shirt-cuff.

It is hard to imagine even an Irvine Welsh novel beginning in such a brazen way. But he turns to narcotics only when there is no brainwork to be had. It helps him ‘escape from the commonplaces of existence.’

He requires constant stimulation of the mind – and when there is none, he either withdraws to his room, in a funk for days at a time, or reverts to his cocaine use. Indeed it seems quite probable evidence that Holmes was a sufferer from bipolar disorder – susceptible to unpredictable mood swings. One minute he is waking Watson in the dead of night to pursue a suspect through the rain, the next he refuses to leave his room for three days.

For the most part, brainwork dominates the stories. Holmes is not the man depicted in the Guy Ritchie/Robert Downey Junior version, swinging from chandeliers like Zorro. Notwithstanding several memorable episodes involving bartitsu, an obscure branch of the martial arts, which involves the use of a cane, and a spot of boxing, he is more commonly found in his mouse-coloured dressing gown, slumped in his chair until the small hours losing himself in a problem

Holmes is not merely a brain on a stick. Nor is he some sort of 19th century superhero. He is an unusual combination of both mental and physical prowess.

To anyone thinking of writing a Sherlock Holmes pastiche. There is one simple piece of advice. Read all of Conan Doyle’s stories first. Yet it transpires that this is not something Conan Doyle chose to do himself. Despite his obvious mastery of plot and character, the books are full of continuity errors.

The mystery of the three dressing gowns.

Holmes dressing gown is described first as blue, then as purple, then mouse coloured. Conan Doyle clearly had better things to do that go rummaging through his old stories to keep things consistent.

Then there’s Dr Watson. Considering he is one of the two main characters, one would have thought that the author would keep a few notes as an aide memoir. But again, Conan Doyle is hilariously inconsistent. In one story the bullet wound he receives in Afghanistan is in the shoulder. In another it is in the leg. This gives the modern writer a dilemma as to which version he is going to use.

In the Man with the Twisted Lip, Conan Doyle even get his name wrong, with Mary referring to him as James, rather than John. (By the way, did you know that Holmes’ sidekick was originally called Ormond Sacker, before settling on John Watson?) And to keep up with Watson’s marriages is beyond the abilities of most.

There is even a Conan Doyle adventure that is set in the years after Holmes death in his tussle with Moriarty but before his resurrection in the Adventure of the Empty House. But if anything, these errors only add to the charm. And as I have found out myself, there is nothing a true Sherlockian enjoys more than pointing out an error. Indeed some have speculated that this was Conan Doyle’s intention – laying mysteries within mysteries. More likely he was churning out the stories at such a rate he didn’t have time to check them properly.

But what is that really appeals about the stories? Undoubtable, there is something in Holmes’ magnetic charisma and he dynamic between Holmes and Watson. Then there is the remarkably stylish prose, the quick as a whip plotting and Conan Doyle’s unique ability to create a vivid sketch of a character in just a couple of lines. Listen to this description of Inspector Bardle of the Sussex Constabulary — he was ‘a steady, solid, bovine man with thoughtful eyes, which looked at me now with a very troubled expression.’ Just a sentence but you get a very complete sense of his character and appearance. This is a remarkable skill, but an essential one for a writer of short stories.

But it is the alchemy of it all working together that makes it such a success. Yes, the adventures are formulaic, but there is wit and invention in abundance. Above all, there is an unusual facility of the language that elevates these stories above the commonplace. Shakespeare used approximately 28,000 unique words. Conan Doyle uses 35,000. He may have been writing popular fiction, but he saw no reason to compromise the quality of the writing.

So what have we learned about Holmes?

He’s a hedonist and man of action, but whose greatest pleasure is brain work. He’s an eccentric who owns three different coloured dressing gowns. He values friendship but has very few. He is detached from his emotions but is capable of feeling great pride and envy. He is blessed with an unusually brave and loyal friend in Dr Watson.

The stories have endured because of the quality of their writing and ingenious plotting. They are full of glamour and decadence – the Victorians and Edwardians enjoyed them in the same way we enjoy watching a James Bond film. But I think it is for the unique dynamic between Watson and Holmes and the quality of darkness and strangeness that the stories continue to appeal.

So, after 130 years, the Holmes phenomenon show no signs of abating. To spend time in the man’s company is to be constantly delighted and confounded.

But have we proved that Sherlock Holmes was imaginary? I’m not so sure. How often has Holmes told us that when you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth?

Christopher James is the author of three Holmes novels, most recently Sherlock Holmes and the Adventure of the Beer Barons.