The Ulysses Diary – Day 8

Bono, that arch doyen of popular song, once said that if James Joyce had remained in Ireland to write Ulysses, he would have talked it away. Written in artistic exile in Paris, Joyce certainly had no problem recalling the Dubliner’s distinctive turn of phrase in this section of the book. The talk at the funeral is a curious mixture of reverence and irreverence. The church caretaker even has time to tell a joke – how a mourner mistakes a statue of Jesus in a foggy graveyard for his late acquaintance. ‘Not a bloody bit like the man’ he says. Joyce makes his own reference to Hamlet to save us the trouble of deciphering the reference to the gravedigger.

Bloom has his own thoughts: ‘Don’t joke about the dead for two years at least’ and yet, he can’t help but find his mind wandering as it does throughout the book. Once again his vanity and jealousies get the better of him: ‘Nice soft tweed Ned Lambert has in that suit.’ The episode is full of stream of conscious and word association mirroring the distracted mind. ‘Far away a donkey brayed. Rain. No such ass.’

He turns from these idle thoughts back to the grave – of the ‘hole waiting for himself,’ and even worries about buried alive, going as far as to devise himself a rescue system, reflecting that there ought to be an ‘electric clock or a telephone in the coffin and some kind of canvas airhole. Flag of distress.’ From such childish footling he suddenly feels a stirring sense of loss for everyone who walked Dublin’s streets before him, invoking their ghostly, collective voice:

‘How many! All these here once walked round Dublin. Faithful departed. As you are now so once were we.’

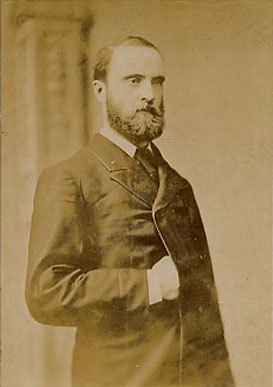

Once again, religion, politics and history rattle like restless phantoms around the narrative; even the great (Charles Stewart) Parnell, the nationalist leader is reduced to ashes. He ‘will never come again’ Hynes says. Bloom considers what grants immortality: a photograph? A scratchy recording on a gramophone? They are flimsy substitutes for the flesh and blood and the spirit of a man.

The episode concludes with the symbol of an obese grey rat, scurrying about in the crypt, ready for the next visitor. It’s a dark, unsettling chapter, musing on death and little else: ‘the saltwhite crumbling mush of corpse.’ Bloom is already well acquainted with death but manages to shake it off for now, thinking of ‘warm beds: warm fullblooded life.’

An unusual word that caught my eye: ‘Chapfallen.’ Taken to mean a unique male version of ‘crestfallen’ implying a certain mid-life weariness.

Pages: 101-117