Now and Then: A potted history of the Beatles’ final songs

As Beatlemania once again reaches fever pitch with the release of Now and Then, the Beatles’ final song together, Chris James looks at the numerous contenders for the Fab Four’s last hurrah.

The End, as we know now, wasn’t the end.

In fact, it wasn’t even the last track on the last record from the Beatles in the 60s: Abbey Road. That honour went to Paul’s throwaway ditty ‘Her Majesty’, which in fact he did throw away before it was rescued from the cutting room floor by a tape operator called John Kurlander, understandably jittery about binning anything by the Fab Four.

Yet Her Majesty wasn’t the final word. Far from it.

Let it Be, with its funereal black cover, was released after Abbey Road in 1970, (although recorded before) meaning there was a whole LP of final songs beyond The End.

The final song on the Let it Be album was Get Back, an unadorned, fresh-sounding rocker (complete with terrific guitar solo from John) bringing the Beatles back full circle to their rock and roll roots. A fitting finale, you might think. Except it wasn’t to be. The actual last song they worked on together (or at least George, Ringo and Paul) was I Me Mine, which needed tidying up before adding to the LP.

The 1970s

Then along came the Hey Jude compilation album later in 1970, a ragtag collection of odds, sods and pearls, pulling together A-sides, B-sides and besides, that had somehow slipped through the clutches of record executives, too busy to notice while fileting perfectly good albums to make less good ones. In their excitement they’d forgotten to swipe these. Making up for lost time, they put this enjoyable but slightly nonsensical compilation together.

The Hey Jude LP ended not with the iconic refrain of its title track, but with the sprightly Ballad of John and Yoko. A breezily busked diary song, it was recorded between Let it Be and Abbey Road and distinguished in that it featured only John and Paul. It gallops along to Paul’s spirited and really rather fine drumming (don’t tell Ringo!) while John noodles with obvious glee, let loose once again on lead guitar.

Again, what a beautiful way to end things: John and Paul, the original partnership, rocking it up for one last hurrah. Then it really was over. Paul fell out with everyone. Lawyers were instructed. Insults (and bricks) were hurled.

John and George formed the next incarnation of ‘The Two-tles’ in 1971 for Lennon’s Imagine album. Like schoolboys smoking behind the bike shed, they collaborated on John’s rather mean-spirited dig at Paul: ‘How Do You Sleep?’ It’s a great sounding track with some career-best playing from George, and an emphatic bass part from Beatles’ alumni Klaus Voormann, but it makes for uneasy listening. John later tried to reinterpret what he meant in the song, but he didn’t sound convincing.

All four Beatles then reunited, after a fashion, to rally behind Ringo on his eponymous 1973 LP. Above-par songs like I’m the Greatest from John, Six O’Clock from Paul and the superb Photograph co-written with George meant that fans could enjoy all the talents once again on one piece of plastic if not on the same song. These too, were all final songs of sorts.

Another contender is the Long and Winding Road. Most would agree this sounds exactly what a Beatles final song should be: a rueful, elegiac look back at their shared history. It finally got its chance to be the final song as the final track on the Beatles’ ‘Blue’ compilation album, also issued in 1973.

Then, for a few years, things went quiet. Then got incredibly loud.

Live at Hollywood Bowl, recorded in 1964-5, but not released until 1977 is essentially an album’s worth of screaming with some songs indistinctly heard in the background. The unresolved seventh chord and Paul’s last shriek on Long Tall Sally then, was the final curtain. It was how they’d often finish their live sets, and so again, with nothing more to give, it was a suitably exuberant, and fitting way to bow out. You can see them now, taking their polite bow while the fans tore the seats from beneath themselves.

Cut to Eric Clapton’s garden on May 19th, 1979. Celebrating the guitarist’s marriage to Pattie Boyd (yes, George’s ex-wife and the same muse who inspired both Something and Layla) George, Paul and Ringo found themselves part of an impromptu, allegedly drunken, Beatles reunion, missing only John. They stumbled through Get Back and Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Heart’s Club Band, before finishing with a pub band bash at Lawdy Miss Crawdy. It was an ignominious note, and poor final song, to end things on.

The 1980s

The senselessness of John’s murder in December 1980 prompted the unthinkable: all three remaining Beatles finally reunited (and sober) on record for George’s tribute to John: All Those Years Ago. It was pleasant enough, but perhaps not the final word people were looking for. For this reason, perhaps that’s why George recorded the superior When We Was Fab (with Ringo on drums) for his masterful 1987 Cloud 9 album.

But with John gone, so too went the prospect of a genuine reunion and new songs. (Paul had already been admonished by John for turning up unannounced at his New York apartment with a guitar, perhaps hoping to rekindle the magic).

So long then, Beatles. Except there were still more final songs to come. Lots more.

The 1990s

The 90s ushered in the Anthology series: three double albums’ worth of giggly outtakes of classic songs, alongside some genuine gold, like McCartney’s demo of Come and Get It, as well as take-it-or-leave-it numbers like the lacklustre If You’ve Got Troubles or the dipsy What’s the New Mary Jane. More last Beatles songs.

Sensing the need to step in and stop this final song madness, re-enter George Martin, their peerless original producer. He declared, once and for all, that there was nothing left in the barrel to scrape.

But hold on! Alongside this alternative history of The Beatles, we were treated to some sparkly ‘new’ recordings: Free as a Bird and Real Love. Lovingly rebuilt around some wobbly song-writing demo tapes John recorded in the 1970s, gifted by Yoko to McCartney), these were transmogrified into bright, tuneful records with cavernous drums, sunshine harmonies and searing slide guitars from George. They didn’t sound like the records the Beatles made in the 60s. For one thing, George didn’t really play slide guitar in the 60s. (The lovely Hawaiian flavoured slide on For You Blue was played by John).

Instead, they sounded like records the Beatles might have made if they’d followed the long and winding road into the 90s and chosen ELO supremo Jeff Lynne as their producer. As the mastermind behind Roy Orbison, Tom Petty and George Harrison’s late eighties career revivals (and great pal of George) Jeff was the right man in the right place with the right sunglasses. And he played a blinder.

The 2000s

But no sooner than the ghosts had been laid to rest, when the news came in 2003 that the Let it Be LP was being ‘de-Spectorised’ and reissued as Let It Be Naked; this time, without the orchestral treacle and uninvited choir of angels added in 1970 without Paul’s consent.

The new version certainly had a raw quality missing from the original, returning it to the spirit of the ‘live only/no overdubs’ promise they’d made at the start of the project. They also reinstated a criminal omission from Let it Be: John’s Don’t Let Me Down, while quietly shoving also-rans Dig It and Maggie Mae off the end of the bench. But what about the final song?

This time, they went for the hymn-like ‘Let it Be’ as the final dignified statement. A comforting reconciliation with friendly ghosts, a coming to terms with the past, it was a healing song of hope and remembrance and the perfect note to end things on.

But as we well know by now, no final song by the Beatles stays final for long. The Let it Be album was transformed again, this time, by Peter Jackson’s magisterial Get Back docuseries. It charmed and astonished us at every turn, and showed that the Beatles didn’t fight all the time in 1969, just some of the time.

The series ended of course, with the inspired rooftop performance, ending on their third run at Get Back. (They practiced that one a lot as anyone who’s watched all 468 minutes will testify). Considering that their hands were freezing on that cold January day in West London, the performances are miraculously tight and soulful.

John’s pronounced: ‘I’d like to thank you on behalf of the group and ourselves and I hope we’ve passed the audition.’ It was the perfect, ironical, good-humoured way to bow out. Or might have been.

The 2020s

Fast forward to June 2023. While chatting amiably to Martha Kearney on the BBC Radio 4 Today programme, Paul casually drops in that he’s been working on a demo from John, and had been using some new technology to clean it up. It had the unmistakable whiff of another final song.

Rewind to 1994-5

The origins were a second tape handed by Yoko to Paul that year, and actually inscribed by John: ‘For Paul’. It contained the song Grow Old With Me (another beautiful tune, but already issued posthumously on John’s 1984 Milk and Honey LP. Putting this final song to one side, and after completing fellow final songs Free as a Bird and Real Love, the Threetles turned their attentions to the new final song: Now and Then.

Slated to open the third of the Anthology compilations, it was shelved after only an afternoon’s work in 1995. Unimpressed by the quality of the demo, hampered by an obstinate ‘mains hum’ that couldn’t be separated from Lennon’s vocals, George Harrison threw in the towel, declaring the demo ‘F*&cking rubbish’. Not even Jeff Lynne had a magic wand powerful enough to take a bad demo and make it better.

Instead, for the new final song on the last Anthology compilation, they added: ‘A Beginning,’ (see what they did there?) a pleasant but ultimately surplus-to-requirements orchestral excursion from George Martin, which originally pre-ambled Ringo’s Don’t Pass Me By from the White Album.

And so that was that. Except, of course, it wasn’t.

Back to the 2000s

Cue the ecstatic chime of the chord of the century that opens: ‘A Hard Day’s Night’ (The Beatles were very good at opening and closing songs). Love was a show and album from 2006: a dizzying, playful reimagining of The Beatles legacy assembled by Giles Martin, who had inherited all of his father’s taste, talent and charm. Accompanying the Cirque du Soleil spectacular of the same name, this was as good as a Beatles album should be. But what about the final song?

This time they went for ‘All You Need is Love as the final unifying anthem: a manifesto statement: Love is all you need. There it was then. The real final song had been there all the time, quietly waiting its turn. As if to underline the point, there was a mischievous little send-off from John spliced in at the end: ‘This is Johnny Rhythm just saying good night to yous all and God bless yous!’

But the Beatles being the Beatles, would insist on a last coda.

Join us back in 2023

Paul made no secret over the years of his intention to complete Now and Then; to: ‘finish it off one of these days.’ And that’s what he and Ringo did, albeit with the full blessing of Yoko Ono Lennon and Olivia Harrison, helped by the magic ears and knob twiddling of Giles Martin, who’s done so much to restore the Beatles’ recordings to their full glory, updating some of the earlier, more eccentric mixes.

But why has Paul felt the need to open Pandora’s box once again? Surely not for the money or to give the reissued and expanded Red and Blue compilations a sales boost. But perhaps because it was so intensely personal. After all, John’s final words to him in person were: ‘Think about me every now and then, old friend.’ This was Paul fulfilling a promise to a dear friend.

Thanks to sound source separation technology (the magic wand Jeff didn’t have in 1995) they’ve finally been able to clean up the tape John left behind for Paul.

Giles has brought his own considerable powers to the party, along with the magic cauldron of the Beatles’ own recordings. With harmonies borrowed from Because, Eleanor Rigby and Here There and Everywhere for the new recording, there’s a tantalizing prospect in store.

Add to John’s still potent writing powers from 1979, Paul’s unmatched musical invention, Ringo’s inimitable drumming and there’s only one man missing: George. Crucially they’ve made full use of that afternoon’s work he put in during the nineties.

The Beatles have had more final songs than number ones. And they’ve had plenty of those: 20 in all. And they’re deserving of another. But maybe this really is the final word.

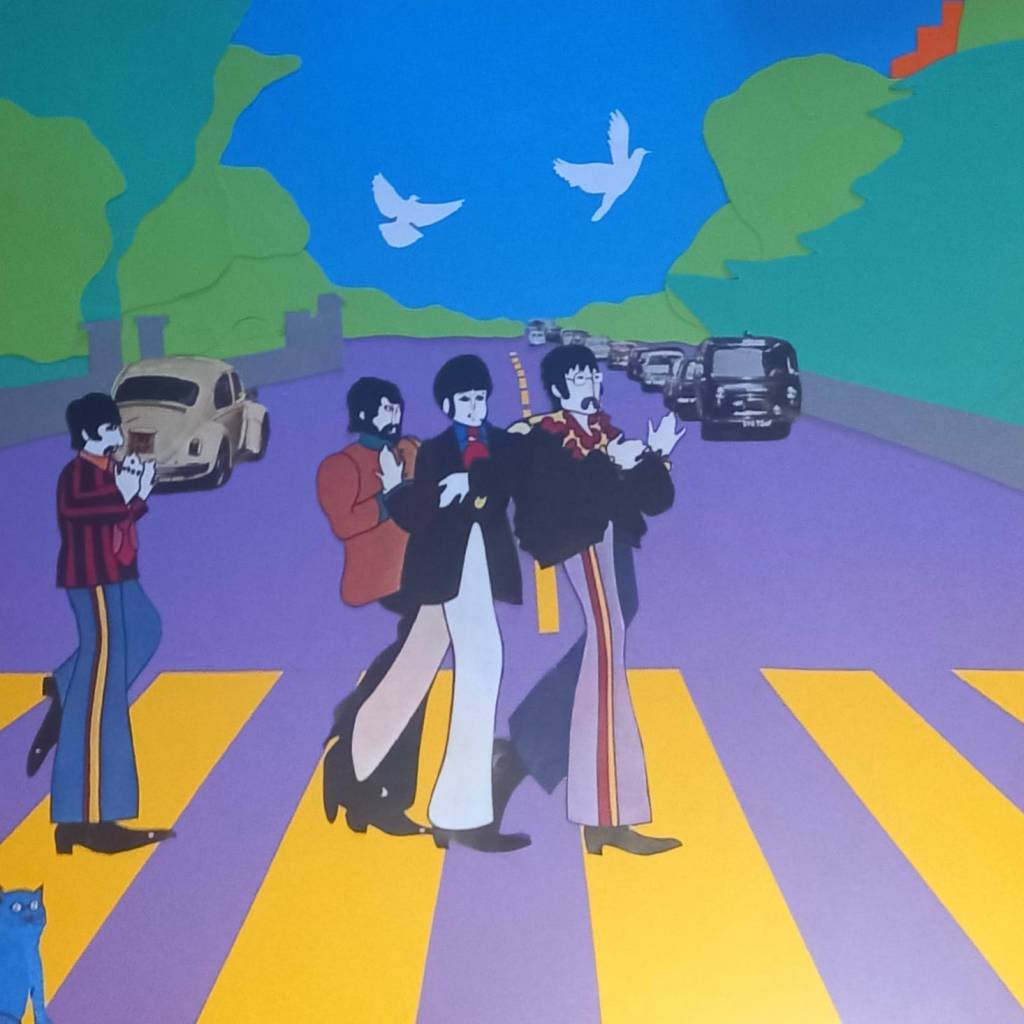

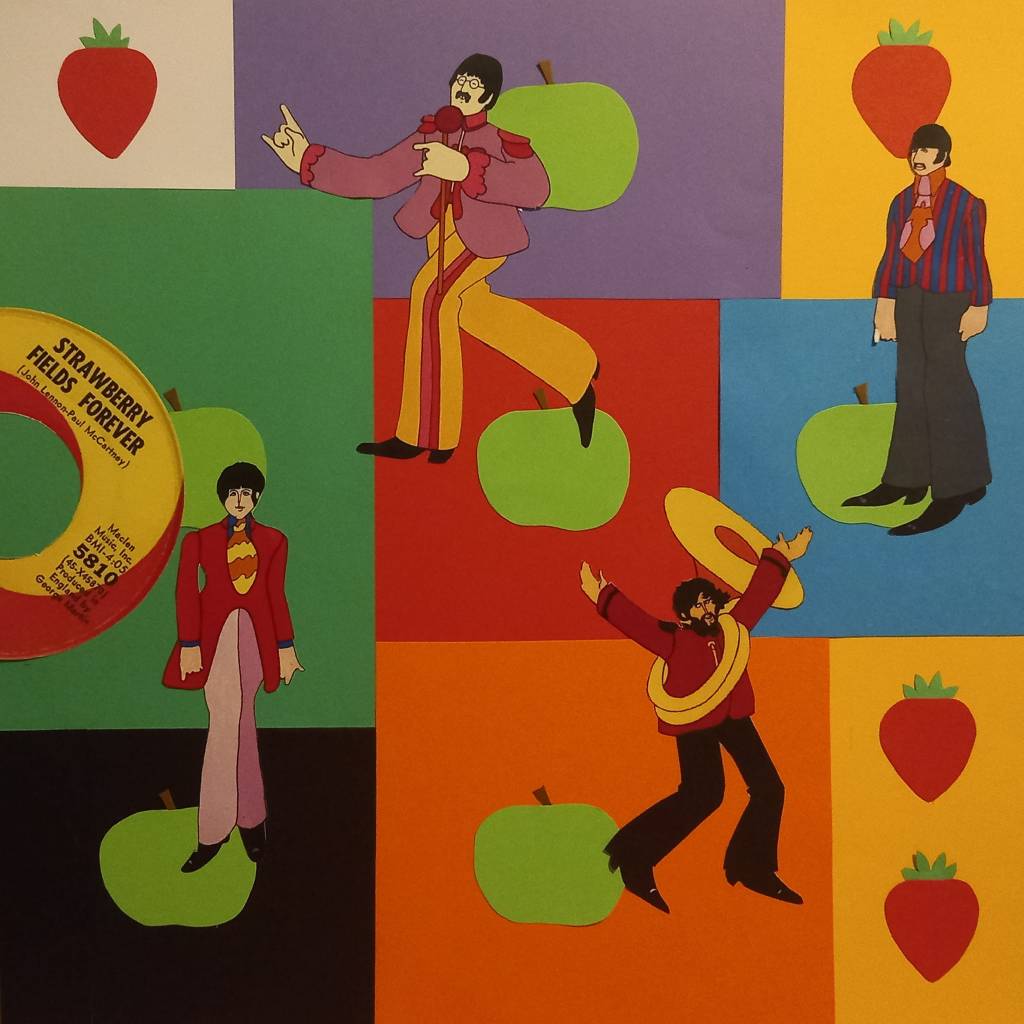

Christopher James is an author, collage artist, and poet. He won the 2008 National Poetry Competition. His latest poetry pamphlet is The Storm in the Piano (Maytree Press, 2022)